- Home

- David Tromblay

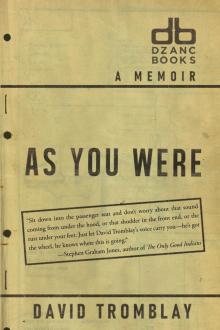

As You Were

As You Were Read online

AS YOU WERE

AS YOU WERE

—A MEMOIR—

DAVID TROMBLAY

5220 Dexter Ann Arbor Rd.

Ann Arbor, MI 48103

www.dzancbooks.org

AS YOU WERE. Copyright © 2021, text by David Tromblay. All rights reserved, except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher: Dzanc Books, 5220 Dexter Ann Arbor Rd., Ann Arbor, MI 48103.

First Edition: February 2021

Cover design by Matthew Revert

Interior design by Michelle Dotter

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

You shall know the truth and the truth shall make you odd.

—Flannery O’Connor, allegedly

OFF THE RESERVATION

YOU COULD BEGIN THIS WITH how Grandpa Bullshit was an arm breaker for the Irish mob in Chicago. Or how the spring of ’68 became the boiling point for the Civil Rights Movement after Dr. Martin Luther King Junior’s murder, shortly after Mom turned eleven. Or how she and all her siblings attended elementary school with the Jackson Five in Gary, Indiana, before they went to Hollywood and the Lynns made their way to the woods in the middle-of-nowhere Minnesota. But it would take too long to give all those details and bring the story back on track. It would be a lot simpler to say how Grandpa Bullshit decided to drive his family here in sixty-eight and did so without making a single pit stop. Instead, he crammed one of those little Porta Potties families take on camping trips into the back of his ’59 Cadillac hearse, along with a couple of suitcases and all six kids.

Six years later, Mom grew tired of babysitting her little brothers and sisters, so she got knocked up and married to get out of the house. Little did she know she’d have to get notes from her husband to excuse her from school once the morning sickness started, despite his being in the same grade. So she dropped out of high school and got her GED because she’ll be Goddamned.

She got divorced from him before she was old enough to register to vote. Three years after she had your big brother Sam, she has you. She takes a taxicab off the Fond du Lac Indian Reservation twenty-odd miles to St. Luke’s Hospital in the east end of downtown Duluth.

You’ll notice there’s no mention of Dad bringing Mom to the hospital, pacing the hallway outside the delivery room while waiting to hear the news, the proclamation of it, you, being a boy. He is elsewhere—with a prostitute. You’ll have to pause here, collect yourself, choke back the laughter. All you can really do is laugh. Not a ha-ha laugh, but a Jesus-jumped-up-Christ-what-could-come-next? kind of laugh—or bite your cheek, or stall, one way or another, before admitting that last bit of information.

Dad doing that might make sense if you were born after midnight on a Saturday, but you were born at about a quarter to four on a Monday afternoon. The real question is: how long should someone go on thinking that’s the worst thing he did that day? Because he made Mom take care of the hooker’s cat while the hooker served a ninety-day jail sentence. He wasn’t charged with a crime. They let him go, according to your mother. According to his mother, he could high dive into a manure pile and come out smelling like roses. He doesn’t go completely unpunished, however; his only begotten son will not bear his last name.

Perhaps hooker isn’t the right word for the woman who kept his company the afternoon you came into the world. She didn’t walk the streets or work a corner. Though the apartments above the Lake View Store—the world’s first indoor mall—where she calls home, do double as a brothel of sorts. Curiously enough, the National Register of Historic Places isn’t in the habit of adorning dilapidated shitholes with copper plaques. And to play devil’s advocate: should it be so surprising to learn the building erected to fill every need of everyone working at the steel mill in Morgan Park, Duluth, Minnesota, did, in fact, sell everything?

Morgan Park came to be for the same reason as Hershey, Pennsylvania, except there are no chocolatiers. When it first opened to the public, the Lake View Store housed a bank, a barbershop and beauty salon, a dentist’s office, a grocery market, as well as a shoe store. And if it hosts the world’s oldest profession now, it certainly did a century ago.

That aside, you’re not special. You’re not the only child to come out of Mom’s second marriage. She had twins—not identical twins, but twins nevertheless. You were a dizygotic twin, meaning each fetus had a separate placenta and a separate amniotic sac. But you grow up thinking you’re their only child. That’s because your brother is stillborn, as was your uncle’s twin, as was your great-uncle’s twin—all on Mom’s side, of course.

Maybe it’s genetic, or happenstance, or the scientific hypothetical sum and substance of someone hanging around a bar, begging her husband to come home, striking up a conversation with the bartender when her husband refuses to move a muscle, and eventually marrying said bartender.

The above is an abridged version of how this happens. How you happen. It’s also from whence the butterfly that peeks out from behind her bra strap came. She got her first and only tattoo one night at a bar while pregnant with the two of you.

There once was an artist who always carried a tackle box filled with tattoo guns and inks and needles, and who was more than willing to tattoo a tit for free on ladies’ night. This, too, explains why your skin is stained with every color of the rainbow—how tattoos got into your blood before birth—like a crack baby, only the addiction is ink. Mom drank and smoked a bit while pregnant, too. It’s easy enough to imagine her Marlboro Reds and the ladies’ night drink specials played into the loss of your brother’s life. At least, they do in the version she told. But in her defense, the doctors didn’t know it was bad for babies back then—or so she said.

You bring up Mom’s drinking and smoking while pregnant—with Bible in hand—and point out a passage, the story of when the Virgin learns she will conceive and give birth to a son. “The angel warns her away from wine and strong drink,” you say. But Mom reminds you, “You’re a son of a bitch, not the Son of God,” and pushes you out of her way with the tip of a wooden spoon, goes back to making dinner, smirking, smiling, laughing at her own joke.

The reason for your twin brother’s birth defect(s) is that all the toxins Mom put into her body went to him first. It sounds bullshitty, but it’s in keeping with the summation the doctor gives after he finishes your football physical and asks if you have any questions. You seize the opportunity to ask what happened to your twin brother.

Mom doesn’t know what they did with him after they took him away. He was medical waste, as far as she knows. Like the placenta and afterbirth. But the doctor should know. He delivered you and cared for you right up until you left for boot camp.

You weren’t born at the Catholic hospital, which has a special plot for all the stillborns and preemies who never get to go home. You were born at the other hospital, so your twin will always be a nameless, missing thing.

Dad never says word one about a twin. When Mom does, it comes out in casual conversation. She assumed someone told you in the decade you lived with Grandma Audrey. The truth of it, and the way Mom tells you, devastates her more than it does you. Learning you shared a womb with a dead kid gives you a lifetime of things to ponder. As does her referring to you as her number two son, wondering whether she merely means you are her second-oldest living son, or if it’s like in the movie Twins, and you’re Danny DeVito in this scenario—the leftover shit.

When your brother came into this world, ruddy yet lifeless, neither she nor the doctor knew you were waiting in the wings. Two weeks after she delivered him, she went back in for a routine checkup to make sure she was still in good health, infection-free, and what h

ave you.

That’s when she found out about you.

She is alone when she learns this. Dad only knows his only son died. He’s out fucking anything he can—even if he has to pay—if only to spread his seed and prove he’s man enough to make a son. This is your SWAG, of course—your Scientific Wild-Ass Guess—but knowing him, and with what’s known about his TBI and the historical happenings of his alcoholic-driven logic, it makes the most sense.

The way Mom tells it, you were a tiny thing tucked up under the right side of her ribcage. She explains how the doctor let her carry you around a little longer. A week or so later, they tried to induce her—but you would not budge. She chuckles when she tells that part of the story, calls you a stubborn little bastard. Shortly thereafter, the sonogram showed you were a sickly child, one losing weight with a heartbeat nowhere near as strong as the doctor preferred. A Cesarean section got scheduled, but you came to town kicking and screaming three days prior.

The cab driver took more than an hour to pick up Mom, but she didn’t give them a call until after she gave up trying to track down Dad. She had her driver’s license, yes, but he took the Duster days before. She took her driver’s test when she was six months along with the two of you. “The guy in the passenger seat thought I’d pop at any minute,” she says. “He looked like he was shitting nickels the whole time, so we were back in the DMV parking lot in less than five minutes. He didn’t mark off a single mistake I made, afraid to give me any anxiety and send me into labor. I had to have the seat so far back I could barely touch the pedals,” she says, and scoots back on the kitchen stool, kicking her legs like Shirley Temple.

Once she checked into the hospital, got placed on a gurney, met with her doctor, and got sent down the hallway toward the delivery room, she finally allowed herself to relax enough to let you into this world.

Your first glimpse of the St. Luke’s Hospital came while she was still on her way to the delivery room but within sight of the double doors. You know, kind of like when you eat some bad Mexican food, and you’re searching for a bathroom, and when you finally catch a glimpse of the porcelain bowl your sphincter lets loose a few feet shy of sitting down.

Mom learned the particulars concerning Dad’s whereabouts while she was still in the hospital but takes her anger out on you. Sweet, less- than-one-week-old, nameless you.

Mom did not christen you with her married name. Instead, she gave you her maiden name: Lynn. Completely understandable. But what gives you trouble in the search for forgiveness is the business of her naming you after the most famous and accomplished man in American history. A newspaperman, inventor, musician, statesman, postmaster, ambassador, and the only non-president to have his likeness etched onto the currency, and the highest denomination at that. Yes, she named you Benjamin Frank Lynn—until Grandma Audrey intervened.

There must be a direct correlation between the absurdity of one’s given name and the age of the parents at the time of their birth. Take those twins from high school, for instance. Phyllis and her brother Phallus. Their mother was seventeen when they were born. He pronounces his name Fay-less, like the shoe store, except with an F. And who could blame him?

But considering who you were named after, you take it upon yourself to inform him his parents named him for a dildo. He can’t take a joke or a punch too well.

Lynn is Irish. It used to be O’Lynn, but Grandpa Bullshit’s grandfather dropped the O. In truth, you don’t know for sure who your grandfather is. You know who Mom called her father. You also know guys get male pattern baldness from their mother’s father, and Grandpa Bullshit died at fifty-one with a full head of hair. Your aunt’s son is grown and has a full head of hair, too. The same as Grandpa Bullshit. But both Sam and you have this full-on George Costanza thing going on. A reverse mohawk. Grandpa Bullshit has an illegitimate child. A daughter. It’s a safe bet her sons have never pored over the instructions on the back of a bottle of Rogaine. It’s a safe bet Grandma Lynn had an illegitimate child too. Let’s call her “Mom.”

Grandma Lynn and Grandpa Bullshit tried for Mom for a good long while.

Any child, really.

Then her mom gifted her a Kewpie doll as if it’d serve as some sort of sycophantic, creepy, fat, naked, winged, kneeling, praying fertility doll with a single curlicue lock of hair atop its head, looking curiously out of the corner of its eye at some unknown thing.

But it worked.

Grandma Lynn got knockd up right after Great-Grandma gifted her the Kewpie. The little cherub was placed on the nightstand and did its magic. Later, Grandma Lynn gifted the Kewpie to Mom, and—tada—here you are.

It’s the only thing Mom left you when she died.

The Kewpie should not be touched unless you want a kid. It should be moved with a pair of salad tongs. No one can really say how that stuff works. Your youngest aunt, the one with the hysterectomy, handles them like an Indian snake charmer. She has a curio cabinet full of them.

Your Kewpie doll isn’t kept on the bedside nightstand. The creepy little fucker is enough to make a guy go limp, plus it’s a reminder of Mom. And who in their right mind wants to think of their dead mother while they’re fucking and trying for a kid? But if you ever do put it to use, it’s probably best to fuck with the lights off.

Note to self.

It’s a safe bet that’s how the other set of grandparents, the ones who raised you, Grandma Audrey and Grandpa Bub, always did it, right? They never lived alone. They always had your big sister, Debbie, and later you under their roof. Grandpa Bub lets out his customary huff of disappointment at everything Dad does and says he does. Grandpa Bub sits silently on the couch, uncrosses his legs, crosses them again, and turns to stare out the window, ignoring Dad, hoping he’ll go away, knowing he never will.

Grandpa Bub won’t say it to Dad’s face, his customary catchphrase he says whenever something burrows beneath his skin, but you know he wants to. You want him to, and in the monotone flatness he uses whenever he wants to joke without coming off as an asshole—the same way he does when the high school lets out and the parade of fatherless, longhaired head-bangers and punks with green and purple mohawks walks by the house.

He stands in the middle of the bay window with his hands on his hips, shaking his head from side to side until the last one trickles by. Grandma Audrey yells at him, “Bub, they can see you!”

He ignores her, says, “If that were my kid, I’d flush it down the toilet,” and, later, “If you tell me what it is, I’ll tell you what to feed it.”

He’s not Dad’s dad. He never fathered any children. He was a virgin until marriage. He was something like fifty years old when he married Grandma Audrey.

When Debbie gets old enough to take Grandma Audrey out drinking to Charlie’s Bar—before it burned and turned into a sodden field where other old ladies take their little kick-me dogs to shit before heading into the vet’s office—she learns a life lesson no one should ever get from an elder.

“What’s this you got me drinking?” Grandma asks.

“Sex on the Beach, Gram.”

“Best damn sex I’ve had in...twenty years,” she says, smacking her lips. “Your Grandpa Bub could fuck a wrinkle all night long and never know the difference.”

She orders another, drinks it, waits until it touches her soul before she tells Debbie how she met her first husband, Grandpa Gene, at a fishbowl party. For the uninitiated, a fishbowl party is where the guys put their car keys in a fishbowl and the girls leave with whoever the keys belong to. That was before he left for the Second World War.

But she backs up a little bit and mentions how she first remembers seeing him at a bowling alley on a league night. A girlfriend of hers was so bold as to brag how no woman could take her Gene away. Grandma got him and got a ring from him. But he wasn’t the only one who gave her an engagement ring. She got engaged to two soldiers and married the one who made it back. Grandma got pregnant with Dad almost as soon as Grandpa Gene came home. Aunt Bobbie came the year

after.

Debbie found Grandpa Gene dead on the shitter about six years before you came to be, so the six-foot-six-inch Swede perched on the living room couch tethered to an oxygen machine is the only one you ever get to call Grandpa. Even though you should call him Granddad, seeing as how it’s him who raises you.

POSITIVE & NEGATIVE

YOUR DAD IS A DICK. How that became a nickname for Richard, you’ll never understand. Rick makes sense, not Dick.

But he is a dick.

He’s bought dream catchers made in Malaysia, for Chrissake. When asked, he tells people he’s a Fugawi Indian. If they don’t get the joke, he puts a hand to his forehead to block out the sun, leans forward, pretends to squint off into the distance, and says, “Where the Fugawi?” in his best Tonto voice.

The internet will tell you the Fugawi are a nomadic tribe that gets lost a lot.

That makes sense, too.

From Dad, you’re Shinnob and Sámi and Innu Montagnais—a little Irish too—which makes you the human equivalent of the swamp water Debbie formulates from the pop machine at the Bonanza all- you-can-eat buffet once you tell her you don’t care what she gets you to drink, so she decides it’ll be a splash of everything: Coke, Diet Coke, Sprite, Minute Maid, Dr. Pepper, and Hi-C. You wouldn’t dare waste it. Waste Grandma’s money, and she’ll haul you out to the parking lot so fast it’ll make your head spin.

Dad put a trailer on a piece of leased land somewhere on the Fond du Lac Indian Reservation, but he isn’t enrolled. He doesn’t have the pedigree for that. His grandparents attended boarding schools. Neither of them ever stepped foot on a reservation again or told their children anything about being Indian. No creation stories nor tales of Wenaboozhoo. He’s like Jack Frost for white people—people like Mom.

An Anishinaabe man took Dad ricing when he was little. Sometimes he points out the spot they went when the two of you motor on over toward the bay. But if you ask him to take you, it’s never the right time of year to knock rice. He mutters how he only went once because the two of them flipped the canoe and sank to their knees in loon shit.

As You Were

As You Were